Chapter SIX

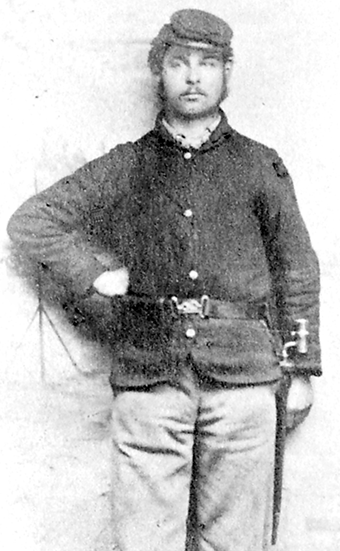

Charles Wellington Reed

21-year-old Charles Wellington Reed

Shortly after 4 o’clock on the afternoon of July 2nd, 1863, bugler Charles Reed¹ reined up on the Abraham Trostle farm two miles south of Gettysburg. Following his lead, horse teams hauling the battery’s six napoleon bronze cannon and ammunition caissons clattered noisily into the boulder-strewn field and slowed to a halt. This Federal unit² was on the verge of its first action of the war, but, for the present, the men and animals could savor a few moments of relative calm.

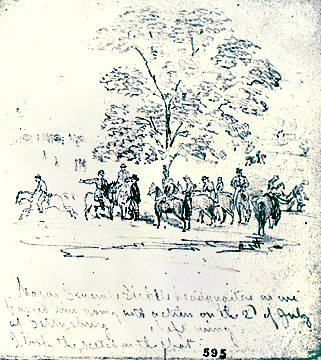

East of them, slightly more than a quarter mile, the struggle for Little Round Top was just commencing. Ignoring the ragged rattle of gunfire and staccato of canon reports, Reed dug a pencil stub out of his jacket pocket and drew a sketch capturing the hectic activity engulfing the field headquarters of General Dan Sickles³. This small rendering became the letterhead for an account of his adventures that Reed mailed to his sister four days later. In it, he succinctly described the scene that inspired his drawing: “At the foot of the hill on which we [later] took position were Major Gen[eral] Sickles headquarters under a tree. We halted here a few minutes giveing [sic] me time to take a sketch of him. One of his Aids [sic] was already wounded by a piece of shell in the back and a surgeon was doing it up.”

When the battery started from Taneytown at dawn, Reed had to leave all his writing materials behind in a supply wagon. He made his sketch on paper scavenged from the remnants of an exploded knapsack he’d discovered along the way. Attempting to draw in the saddle would have been very difficult. Perhaps, Reed tethered his horse to the wheel of a caisson, climbed atop its broad oak chest, and employed its lid as a drawing table.

Reed described his sense of detachment at this juncture to his sister, “I must say I was surprised at myself in not experiencing more fear than I did[,] as it was it seemed more like going to some game or a review.” The brief respite concluded, the battery commander4 directed Reed to signal the command “Forward.” Reed stuffed his sketch into his kit and blew the terse notes that ordered the battery into the crucible of its first combat.

Early that morning, General Meade5 had directed Sickles to post the 3rd Corps along a line extending south down Cemetery Ridge from the left of the 2nd Corps to the base of Little Round Top to anchor the left of the Union line. Sickles didn’t like the low ground of this position, and at 3 o’clock in the afternoon had moved his entire Corps forward a half-mile to the higher ground along the Emmitsburg Road. He hadn’t sought Meade’s permission before he relocated his Corps, and failed to inform him of it after the move had been completed. His flagrant insubordination might have cost Meade his army.

Nor did Sickles make any attempt to inform the commander of the 2nd Corps6 of this movement, which left Hancock’s flank dangling “in the air” and left a gaping hole in the Union line. Still worse, the ill-conceived deployment contained an extremely vulnerable salient at the junction of the Emmitsburg and Wheatfield roads.

Charles W. Reed’s sketch of Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles’ field H.Q.

In an attempt to shore up this exposed “dog leg” in his line, Sickles managed to assemble a force of no fewer than 38 artillery pieces which were bunched along the two sides of this obtuse angle. Bigelow’s battery anchored the left flank of this makeshift defense which lacked any infantry support. Across the road up a rise, stood a peach orchard. A forested, jagged hillock rose opposite their front and there was a field of wheat off to the left.13

The guns lining this salient were immediately exposed to enfilading fire from masked Confederate batteries situated on higher ground. Except for the minimal protection the contours of the ground afforded, there was no cover whatever. In Bigelow’s battery, Lt. Christopher Erickson was almost immediately struck in the chest by shrapnel and Bigelow ordered him to the rear to have his injury treated. Sometime later Erickson returned to his guns. Bigelow assumed he’d recovered, but Erickson’s lung had been punctured and he was slowly bleeding to death.

The Federal batteries probably “gave as good as they got” while counter-battery fire was all they had to contend with but, once McLaws’8 division of Longstreet’s9 Corps began its assault, the position quickly became untenable and they had to abandon the field or lose the guns.

Bigelow’s battery was the last to go. Kershaw’s10 troops storming north were almost upon them, and Barksdale’s11 Mississippians were slashing at them from the west. Afraid that he’d lose his guns if they stopped firing long enough to “limber up,” Bigelow ordered that they be hauled off by prolonge (ropes tied from the gun’s trail to the limber). This maneuver allowed the gun crews to keep firing as the cannons were pulled away and the recoil assisted in propelling them along. When the battery reached the Trostle farmhouse, Col. McGilvery12 waved it to a halt. Six-hundred yards east of them lay the gap in the Union line created by Sickle’s ill advised redeployment.13

McGilvery told Bigelow he needed time to locate some artillery to fill this hole or it could spell disaster. The 9th had to buy him that time even if it meant sacrificing the battery. “Hold at all hazard!” was the odious demand he placed on Bigelow.

Dutifully, Bigelow set about preparing his command for the Rebel onslaught. With no other options at his disposal, he placed his guns inside the corner of a waist-high rock wall fanning them out in a crescent to create the widest possible field of fire. When the men of Barksdale’s 21st Mississippi rose waist high above the crest of a rise less than seventy-five yards away, the right section blasted them with double loads of canister.14 To avoid this fire, Barksdale’s men passed behind the Trostle barn and farmhouse to get on Bigelow’s flank. Similarly, Kershaw’s men advancing from the south veered east and gained the battery’s opposite flank.

During this brief sharp encounter, the battery suffered devastating losses. Bigelow described the action: “Sergeant after sergt. was struck down, horses were plunging and laying all around, bullets now came in on all sides for the enemy had turned my flanks. The air was dark with smoke.”

When Bigelow finally saw Union batteries forming several hundred yards in the rear, he decided his men had done enough and it was time to go. He ordered the two guns on the left off first. While the other four guns kept up fire, the first limber passed behind them and drove through a narrow gate into the farm lane. It cut too sharply and the gun toppled onto its side blocking the exit. It required several minutes for the crew to right it. The second gun decided to try and vault the rock wall rather than wait. Before the attempt, its gun-crew madly tore away stones trying to lower the hurdle’s height. Accompanied by Reed, Bigelow rode over to urge them on. The two horsemen made conspicuous targets. Several Confederates took aim and fired a volley at them. Reed saved himself by yanking his reins back setting his horse on its haunches, but the fusillade struck Bigelow and his horse. The injured steed cantered off about a hundred feet where Bigelow tumbled to the ground, shot through the waist.

As horses and gun-crew struggled to heave the limber and gun over the wall, Reed rushed over to his fallen commander. With the help of Pvt John Kelly, Bigelow’s aide, the two men shoved Bigelow up into the saddle of Reed’s unwounded mount. Reed climbed aboard Kelly’s horse and grabbing the reins of both steeds in his left hand and holding Bigelow in the saddle with his right, he began urging his charges back toward Cemetery Ridge following in the wake of dust clouds raised by the battery’s escaping guns.

Around this time, the remaining four guns of the battery had to be abandoned. There weren’t enough horses left to bring them off, and the Rebel troops were swarming over them. During the final moments of the fight, the courageous Lt. Erickson was shot twice in the head, and died instantly. Lt. Alexander Whitaker, another section leader, took a ball in the knee, but was able to keep to his horse. Hoping to prevent the Confederates from turning the captured cannons on them as they dashed away, Bigelow’s men spiked the ones they could and carried away the friction primers, water buckets, and ramrods.

Reed and Bigelow’s ordeal hadn’t ended. Their slow progress put them between the fire of Confederates in their rear, and the guns that McGilvery had stationed several hundred yards in their front. Halfway to the nearest of these batteries one of its officers rode up urging them to hurry so they could open fire on the Confederates that were rushing forward from the Trostle farm. Bigelow said that he couldn’t travel any faster and urged him to, “Fire away!”

Soon after the officer spurred off, the battery opened up with double loads of canister. In a bid to avoid hitting Bigelow and Reed, the battery’s left section elected to fire shell instead of canister until they’d passed between its guns. Miraculously, Reed managed to steady both horses and keep Bigelow in the saddle while they suffered the ear-splitting reports, scorching blasts, and geysers of smoke belching from the muzzles. After a few more perilous moments the party passed through the battery and on to safety.

The twenty minutes Bigelow’s battery managed to delay the Confederate advance let McGilvery patch together “The Plum Run Line,” a ragtag assemblage of artillery pieces numbering no more than 25 guns, which managed to fend off the Rebel advance until Federal infantry arrived.

The heroic stand of the 9th Mass. Battery helped save the Union army from a calamity, but it had cost them dearly. Ten men were killed, another fifteen had been seriously wounded, two were captured, four guns were lost (though recaptured), and no fewer than sixty-nine of its eighty-eight horses had been killed or wounded.

Of the roughly 193,000 combatants that participated in the battle, Reed is the only one known to have created a visual record of the action during the three-day inferno. In recognition of the selfless courage he displayed saving his commanding officer’s life and preventing his capture, Reed was awarded The Medal of Honor. These two remarkable achievements mark him as the most unique of the Artists at Gettysburg.

1 Corp. Charles Wellington Reed was 21 years old.

2 9th Independent Battery, Massachusetts Light Artillery

3 Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles, commanding 3rd Corps, Army of the Potomac

4 Capt. John Bigelow

5 Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, commanding, Army of the Potomac

6 Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, commanding 2nd Corps, Army of the Potomac

7 The vicious encounters that engulfed The Wheatfield, Stony Hill, and Peach Orchard insured that these names would be forever etched into the battles lore.

8 Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, division commander, 1st Corp, Army of Northern Virginia

9 Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, commanding 1st Corp, Army of Northern Virginia

10 Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw, commanding Kershaw’s (South Carolina) Brigade

11 Brig. Gen. William Barksdale, commanding Barksdale’s (Mississippi) Brigade

12 Lt. Col. Freeman McGilvery, commanding Artillery Reserve, Army of the Potomac

13 The precise location Meade had assigned the 3rd Corps before Sickles ignored his orders.

14 A canister round carried twenty-seven 1.5” lead shot stacked in four tiers. In effect, it was a giant shotgun round designed to scythe swaths through dense ranks of infantry.