Chapter Two

Alfred R. Waud

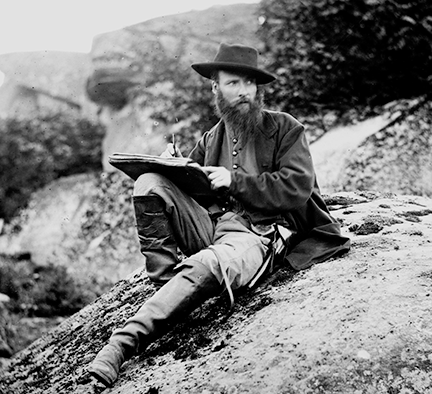

Alfred Waud sketching while seated on a boulder in Devil’s Den, July 5, 1863

During the Civil War, Northern and Southern newspapers combined to send nearly five-hundred correspondents into the field to cover the action. The vast majority of these reporters were writers, but a few score were “special artists.” “Specials” were tasked with creating images of the war that would excite and inform the general public. The pictures these artists sent back were converted into wood engravings that illustrated every aspect of the conflict for the newspaper’s readers.¹

Alfred Waud² (pr. Wode) was clearly among the most gifted and prolific members of this small cadre of visual reporters. Today, the works he created are acclaimed for their artistic merit, but at the time it’s doubtful anyone outside the newspaper industry even saw them. They were regarded as “rough drafts” — guides for engravers³ — not artwork. Had the general public seen his originals, Waud’s deft sketches would probably have appeared foreign and unfinished to Victorians grown accustomed to stylized, formulaic, heavily-finished works of art.

Waud’s fluid style excelled at evoking the immediacy and drama of a fleeting moment, giving it a contemporary look.4 Unfortunately, none of this vitality or excitement managed to survive the heavy-handed interpretations of the newspaper’s engravers. The only components of Waud’s evocative artwork that survived this treatment are his careful observation and his imaginative compositions.

As is evident in the photograph Timothy O’Sullivan took of the artist at work seated on a boulder in Gettysburg’s Devil’s Den, Alfred Waud had a flair for the theatrical. In an era noted for colorful characters, Waud managed to standout. In 1864, a fellow Englishmen set down this impression, “Blue eyed, fair-bearded, strapping and stalwart, full of loud cheery laughs and comic songs, armed to the teeth, jack-booted, gauntleted, slouch-hated, yet clad in the shooting-jacket of a civilian.”

The swashbuckling image Waud promoted wasn’t mere braggadocio. While other artists were content to use a telescope or binoculars to observe the action from a distance, he regularly exposed himself to shot and shell in order to obtain a firsthand picture of the action. A man with “sand,” especially a civilian, was greatly admired in the Union army. Waud’s willingness to place himself in harm’s way, together with his conviviality, earned him the trust and friendship of many high-ranking Union officers. Waud’s close association with its elite netted him better meals and more comfortable accommodations than those endured by most reporters.

When war broke out in April 1861, Waud was thirty-three years old with a wife and children. His decision to voluntarily leave his family behind to become a war correspondent is puzzling. As a British citizen,5 he couldn’t be drafted, and no one would have expected him to volunteer. Many young men who wanted to fight, especially those who’d never traveled more than a few miles from the family farm, were convinced the war would provide them with the grandest adventure of their lives. As they phrased it, they wanted to “See the Elephant.” Waud too may have found the lure of adventure simply irresistible.

It’s never been determined exactly when Waud arrived on the Gettysburg battlefield, but it may have been as early as the morning of the first day’s battle. Just after ten o’clock that morning, Major General John Fulton Reynolds, commanding the Left Wing of the Army of the Potomac, was shot and killed. Waud drew three different versions of Reynolds’ death, and wrote a lengthy commentary about the incident on the back of one of these drawings (See Appendix A) which suggests he may have been in the near vicinity when it occurred.

1 Thousands of photographs were taken of the Civil War, but the lengthy exposure time the cameras required prevented their capturing action, and there was no method of mass producing a photos’ tonal image on the printed page.

2 Waud’s associates called him “Alf.” At the outbreak of hostilities, Waud went to work for the New York Illustrated News. Early in 1862, Harper’s Weekly lured him away.

3 Regarded as little more than disposable “first steps” in the engraving process, it’s a marvel the Library of Congress’ archive of Waud’s Civil War art contains more than 1,200 original sketches of the war.

4 In France, The Impressionists were also developing stylistic means of conveying the transitory nature of “the moment” (Impressionism)

5 Waud was born in London, England, October 2, 1828. After studying art and working as a theatrical scene designer, he immigrated to America in 1850. He began his newspaper work transferring drawings onto woodblocks for engravers in Boston, Massachusetts.