Chapter FOUR

Bayard Wilkeson

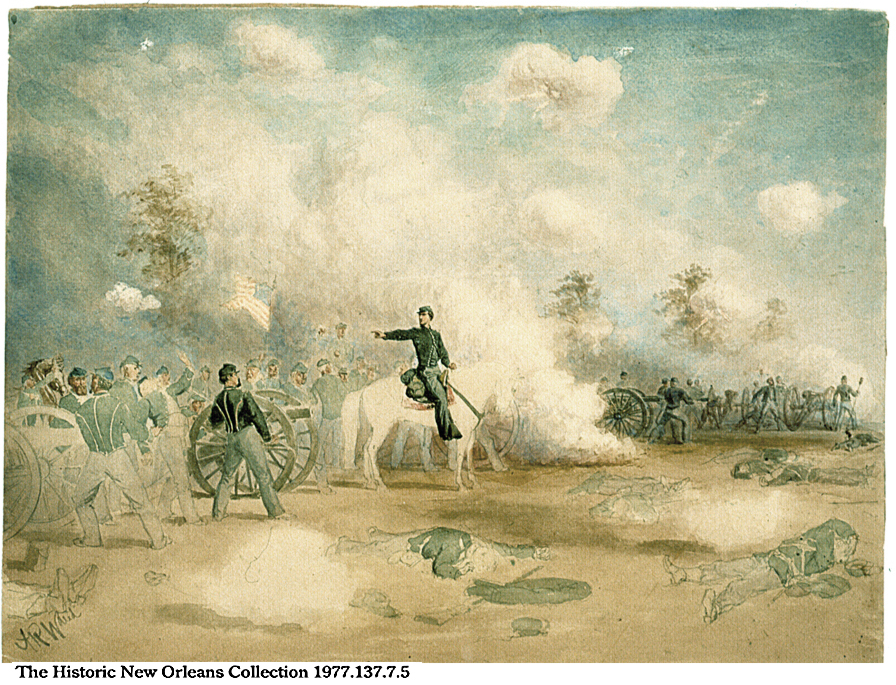

Unfinished Waud watercolor of Bayard Wilkeson’s battery in action, morning of July 1st, 1863

In the early afternoon of the first day’s battle, nineteen-year old Lieutenant Bayard Wilkeson led his four gun artillery battery through the streets of Gettysburg into the fields north of town. Reporting to Brigadier General Francis Barlow near the county almshouse, Wilkeson was informed that Barlow’s division formed the right end of the 11th Corps’ line. Fearing an attack on his exposed right flank, Barlow pointed to a slight elevation about a quarter mile away and ordered Wilkeson to take his battery there. It was an ill-advised tactical decision that cost Bayard Wilkeson his life.

After posting the battery’s bronze “Napoleons” on the knoll, Wilkeson ordered them to commence firing. Two Confederate batteries immediately responded with an accurate enfilading fire. In the words of an eyewitness, “almost at first fire” Wilkeson was struck by a shell fragment that nearly ripped off his right leg. Lying on a blanket while propped up against a tree, Wilkeson employed his sash as a tourniquet and amputated the shredded remains of his lower leg with his pocketknife. The operation complete, he continued to direct fire until carried back to the almshouse that was serving as the 11th Corps field hospital.

When two brigades of Richard Ewell’s Corps came booming down the Heidlersburg Road behind Barlow’s right flank, his division’s position became untenable, and the rout was on. Rather than accept the responsibility for his own flawed tactics, Barlow unfairly blamed the ensuing disaster on the unreliability of his men: “The enemy skirmishers had hardly attacked us before my men began to run.” The collapse was so precipitous there was no time to remove the wounded from the almshouse, and Wilkeson was left behind, where he later died.

Barlow was shot in the chest and was left behind as well. Following up the Federal retreat on his jet-black charger, Confederate Brigadier General John Brown Gordon saw Barlow lying on his back dreadfully wounded. He dismounted and gave Barlow a drink from his canteen. Believing that his wound was fatal Barlow begged Gordon to inform Mrs. Barlow that her husband’s dying thoughts had been of her.

When Gordon asked for her address, Barlow told him that his wife had accompanied him on the campaign and was close at hand. That night a note was sent into the Union lines under a flag of truce informing Barlow’s wife that he was mortally wounded and a prisoner, and offering her safe passage through the lines if she would care to visit her dying husband. After seeing that Barlow was removed from the field on a litter, Gordon returned to the fighting.

Fifteen years passed before Barlow and Gordon met by chance at a Washington dinner hosted by a mutual friend. In the interim, both had assumed that the other had died in the war. When the two men were reintroduced Gordon asked in surprise, “General are you related to the Barlow who died at Gettysburg?” and Barlow answered with perfect aplomb, “I am the man, sir!”

Bayard Wilkeson’s father, Samuel Wilkeson II, was a reporter for the New York Times. He arrived in Gettysburg on July 2nd to learn that his son had been wounded. It wasn’t until 2 days later, when he went to the almshouse, that he learned his son had died. In the hyperbolic style of the time, he poured out the torment he was feeling in his report sent to the Times later that day: “Who can write the history of a battle whose eyes are immovably fastened upon a central figure of transcendingly [sic] absorbing interest – the dead body of an oldest born, crushed by a shell in a position where a battery should never have been sent, and abandoned to death in a building where surgeons dared not to stay? My pen is heavy. Oh, you dead, who at Gettysburgh [sic] have baptized with your blood the second birth of Freedom in America, how you are to be envied! I rise from a grave whose wet clay I have passionately kissed, and I look up and see Christ spanning this battle-field with his feet and reaching fraternal[sic] and lovingly up to heaven. His right hand opens the gates of Paradise — with his left he beckons to these mutilated, bloody, swollen forms.”

The Historic New Orleans Collection 1977.137.2.5_o2

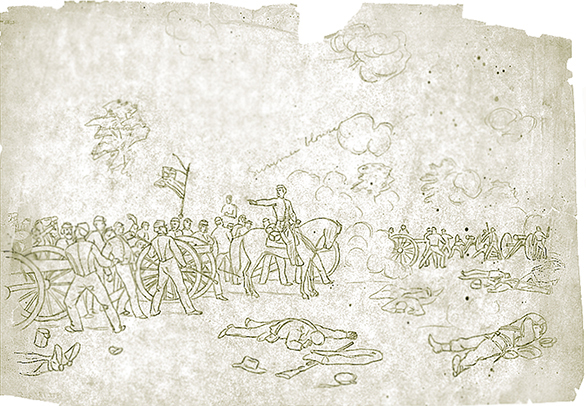

While this may appear to be a preliminary drawing for his unfinished watercolor, the notation, “summer blouses” suggests it was originally one of Waud’s Gettysburg scenes created for use in Harper’s Weekly.