Chapter THREE

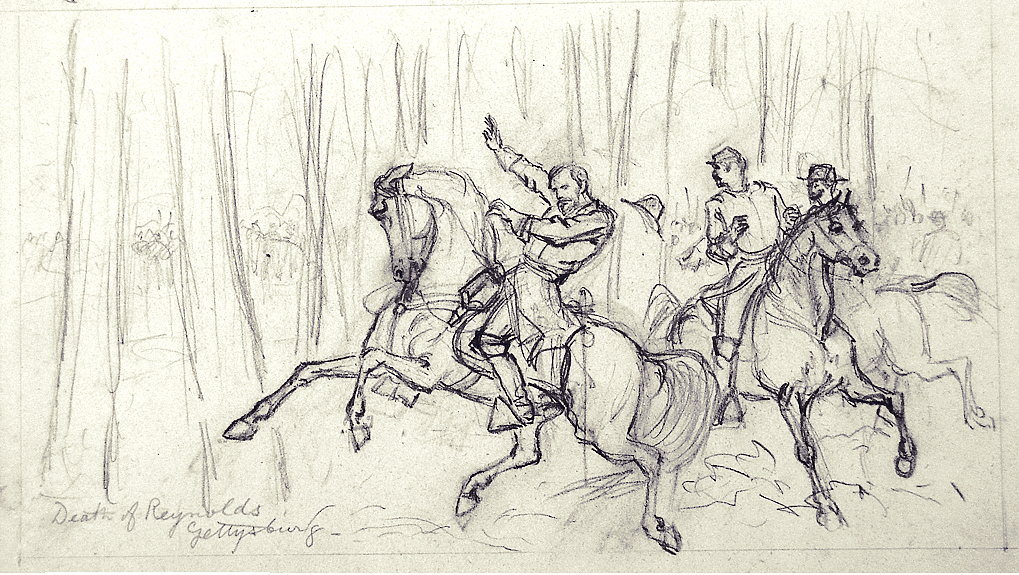

The Death of Reynolds

Sketch by A. R. Waud

After successfully completing his urgent mission, Maj. Gen. John Reynolds¹ rode back onto Seminary Ridge shortly before 10 o’clock the morning of July 1st 1863. A half-hour earlier, he’d ridden out of Gettysburg, heading south down the Emmitsburg Road where he’d intercepted a battery of Union artillery and two brigades of infantry² trudging toward its outskirts. He informed their commanders that these units were desperately needed to support Union cavalry engaged in a fire-fight a mile out of town. Directing that they head toward the smoke of battle rising above a ridge northwest of them, he’d sent this cavalcade hustling off across fields left of the road before galloping back through town with his small party of aides in tow.

During a reconnaissance he’d conducted with Brig. Gen. John Buford³ earlier that morning, Reynolds had learned that a strong Confederate force was marching east on the Chambersburg Pike heading for the small hamlet. Buford told Reynolds that his videttes had engaged Rebel pickets shortly after sunup over three miles west of the ridge they were standing on. Armed with repeating carbines and fighting on foot, his cavalrymen had managed to mount a stubborn defense that had bedeviled the Rebel advance for nearly two hours.

Exercising his authority as commander of the Left Wing of the Army of the Potomac, Reynolds decided to make a determined stand against these lead elements of Lee’s army4 in a bid to give Meade5 time to consider his options and bring up the rest of his forces should he choose to do so. Exhorting Buford to hold fast until his return, he’d galloped off in search of reinforcements.

As Reynolds watched the relief column he’d commandeered arrive, Cpt. Hall, and shortly thereafter, Gen. Cutler, reported to him for orders. He told Hall to plant his artillery beside the Chambersburg Pike where it passed over West McPherson Ridge.6 Cutler was to post two regiments near the McPherson farm buildings in support of Hall’s left flank. The bulk of his command was to proceed to the open fields north of an abandoned railroad cut running parallel to the Pike, and form a battle-line fronting west.

Wanting to confirm that his orders were being carried out to his satisfaction, Reynolds rode out to West McPherson Ridge.

Though visibility was obscured by smoke from Hall’s guns, he soon spied Rebel infantry crossing Willoughby Run, a shallow creek running along the base of the ridge, and working their way up into Herbst’s Wood, a stand of timber located about three hundred yards due south of Hall’s position. Reynolds was appalled! Both Hall’s battery and Cutler’s entire brigade were in danger of being out flanked! Signaling for his aides to follow, Reynolds raced back to East McPherson Ridge hoping to find that the “Iron Brigade” had reached the field and was ready for the fight.

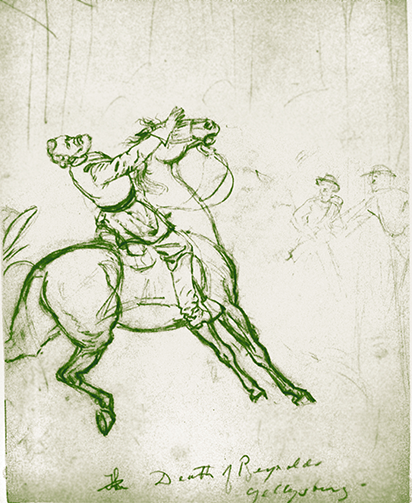

Sketch by A.R. Waud

Waud produced several dozen drawings of the Gettysburg battle. However, the only incident he drew more than once was that of Reynolds’ death. It’s possible he was in the near vicinity when this occurred, as his penchant for being “on-top-of-the-action” is well documented. Perhaps, he sat on the Seminary steps taking a sketch as he watched the action unfold through field glasses. Depicting this agonizing loss in three different views may have been his way of coping with the anguish it had evoked.

To his relief, he found Meredith’s command hurrying down the western slope of Seminary Ridge with four regiments strung out to the south in an “echelon” formation.7 Units which had not halted along the route to load their weapons jostled along at the double quick trying to do so. Shouting for the commander of the lead regiment to follow him, Reynolds wheeled his mount around and charged back up the steep slope. After the 2nd Wisconsin reached the crest, he led them into the timbered down slope. While moving forward they opened fire on the advancing Rebel line and received their answering volleys in return. Shortly after entering the woods a projectile hit Reynolds behind his right ear and moments later he plunged to the ground. His aides quickly dismounted and carried his motionless body out of the woods preventing its capture by nearby Rebel infantry. By the time this party reached the Seminary, Reynolds was dead.

Nearly every account of these events written from the Union perspective states unequivocally that the wound Reynolds received to the back of his head resulted from his having been turned away from the fighting when he received his mortal wound. In a commentary he sent his editor at Harper’s Weekly written two days later, Alfred Waud made this very claim. (See Appendix A).

Sketch by A.R. Waud

None of the compelling images that Waud created of Reynolds ever appeared as illustrations in Harpers Weekly. The editor may have wagered his readers would rather be regaled with news of Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg than be reminded of the victory’s cost.

Considering the utter bedlam that had erupted together with the smoke from several volleys which blanketed the woods obscuring vision, it’s extremely doubtful anyone saw Reynolds when he was struck. In an effort to determine what was more likely to have occurred, I examined numerous contemporary accounts, official reports, and histories devoted to The Battle of Gettysburg. The findings I derived from this extensive analysis are contained in “Enduring Tales of Gettysburg: The Death of Reynolds,”8an article I wrote for Gettysburg Magazine. This study notes that the most reliable sources locate him riding somewhere between the lines when struck behind the ear. Taken together, these two facts present a strong argument for Reynolds having been killed by accidental “friendly fire” rather than enemy action!

Commencing with Waud, these early chroniclers adopted a narrative intended to keep this horrendous possibility from ever being addressed. They insisted that Reynolds had either been riding away from the enemy when struck, or that he was looking back over his shoulder toward the Seminary. Numerous authors seeking to invest this far more palatable narrative with additional authenticity, followed Waud’s lead by indicating a location for the phantom marksman. One preposterous account even claimed the distance of this deadly shot measured over 800 yards!

Though the argument of whether Reynolds was killed by “friendly” or “enemy” fire will probably never be resolved, it’s beyond refute that the loss of the commander of the Union army’s Left Wing at the very commencement of the battle he was directing was a tremendous setback for the Federal force. The blow this dealt the Union command structure clearly hampered Meade’s ability to develop a plan of battle, and might even have proven significant enough to grant Lee the victory. Fortunately, this was not the case. After three bloody days of fighting, Lee’s army was forced to withdraw, and The Army of Northern Virginia never managed to cross the Potomac again.

1 Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds, Commander 1st Corp; Commanding Left Wing, Army of the Potomac

2 Cpt. James A. Hall’s Maine Light, 2nd Battery (B):

Brig. Gen. Lysander Cutler’s, 2nd Brig., 1st Div.,1st Corp;

Brig. Gen. Solomon Meredith’s, 1st Brig.,1st Div., 1st Corp

3 Brig. Gen. John Buford Commander 1st Division Cavalry

4 Maj. Gen. Robert E. Lee, Commander Army of Northern Virginia

5 Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, Commander Army of the Potomac

6 The topography of the terrain west of the Lutheran Seminary is extremely undulating and marked by numerous ridges lying roughly parallel to one another along a north-south axis. Situated approx. 1/4 mile west of Seminary Ridge, McPherson ridge separates into two arms as it emerges from the northern edge of Herbst Wood. A shallow depression less than 30 feet deep lies between the East and West portions of the ridge.

7 Brig. Gen. Solomon Meredith’s “Iron Brigade” was arrayed as follows: The 2nd Wisconsin followed on its left by the 7th Wisconsin, 19th Indiana, and finally the 24th Michigan. Their “echelon” formation meant that each regiment was positioned off the left flank of, and some distance behind, the regiment to its right. The 6th Wisconsin was held in reserve near the Seminary.

8 Gettysburg Magazine, Morningside Press, Issue #14, January 1996