CHAPTER FIVE

Portfolio of Alfred R. Waud

Zoom in or use your browser’s magnifier to see greater detail of drawings.

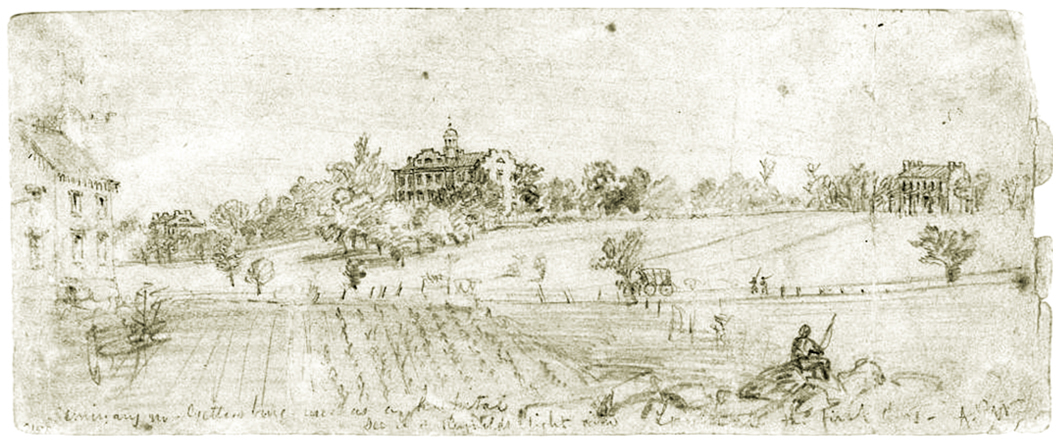

Seminary nr. Gettysburg used as a hospital, scene of Reynold’s fight with Longstreet the first day.

This view of the Lutheran Seminary is looking southwest at the eastern slope of the ridge. In their chaotic retreat on the afternoon of the first days fighting, Union soldiers stumbled over this landscape in total disarray as they attempted to reach the safety of fallback positions on Cemetery Hill. During this precipitous escape, Federal gun batteries clattered to safety down the Chambersburg Pike (seen in the near ground).

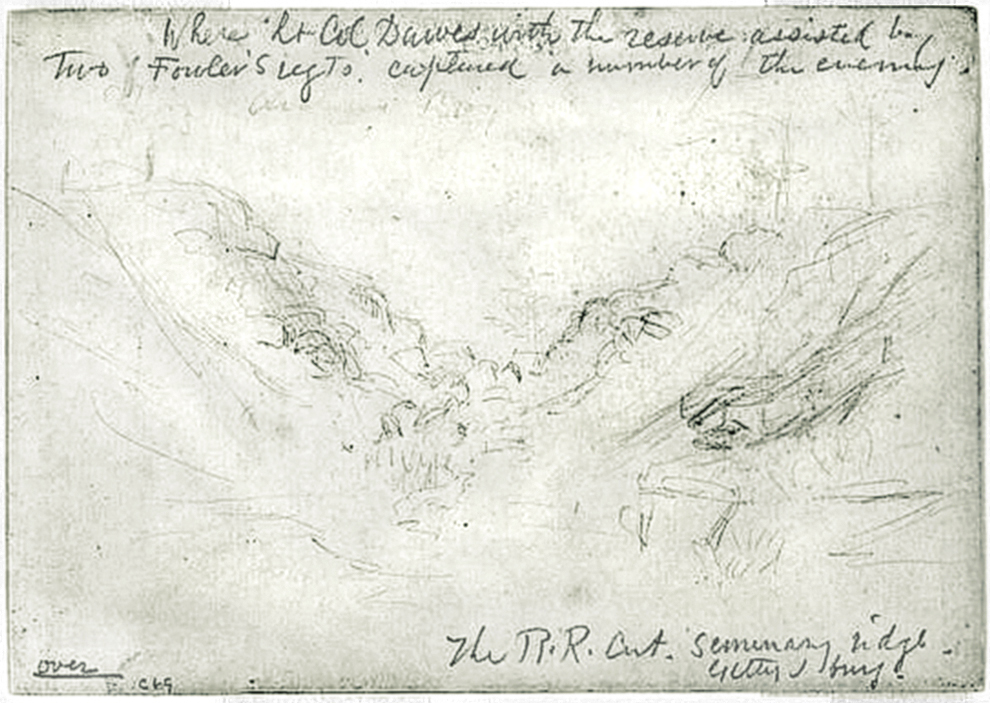

Where Lt. Col. Dawes with the reserve assisted by Two Fowler’s regts. captured a number of the enemy

the R.R. Cut Seminary ridge, Gettysburg

As these two drawings above and below demonstrate, Waud frequently made a quick sketch adding written notations as a way of “fixing” the salient details of a scene which he’d later refer to while producing a second version containing greater detail.

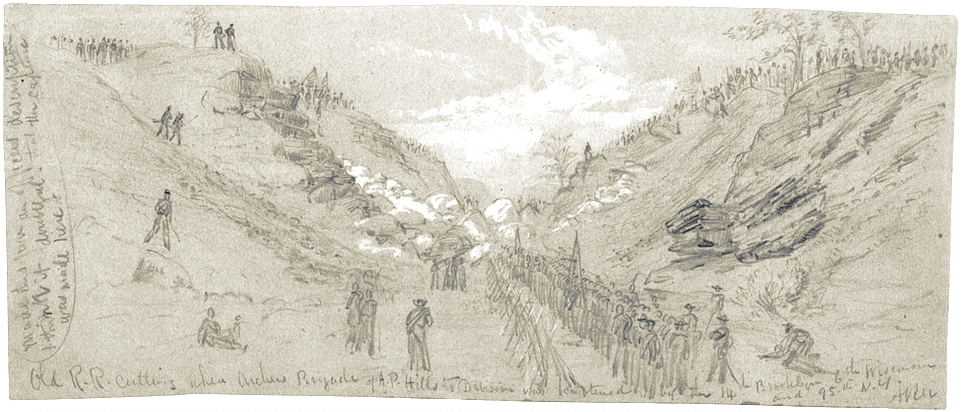

Old R.R. Cutting where Archers Brigade of A.P. Hills Division was captured by the 14th Brooklyn 6th Wisconsin and 95th N.Y. / Written vertically: Made this from an officers description. I think it doubtful that the capture was made here.

Waud was correct in questioning the location of the R.R. cut fight. It took place further west just beyond where the grade passes beyond Seminary Ridge. Rebels from Joseph Davis’ command were captured in the R.R. cut, not Archer’s Brigade.

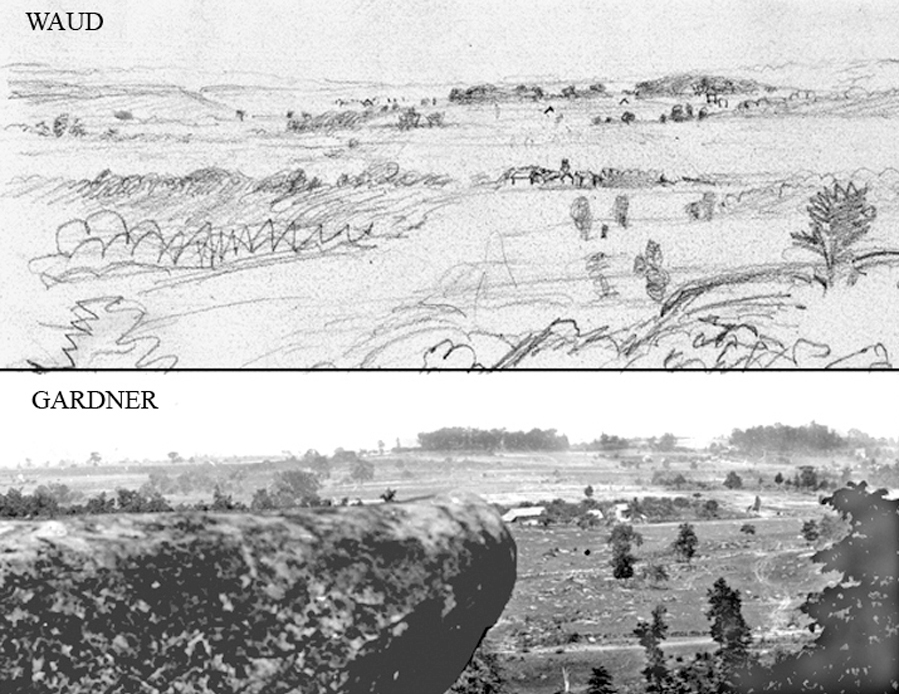

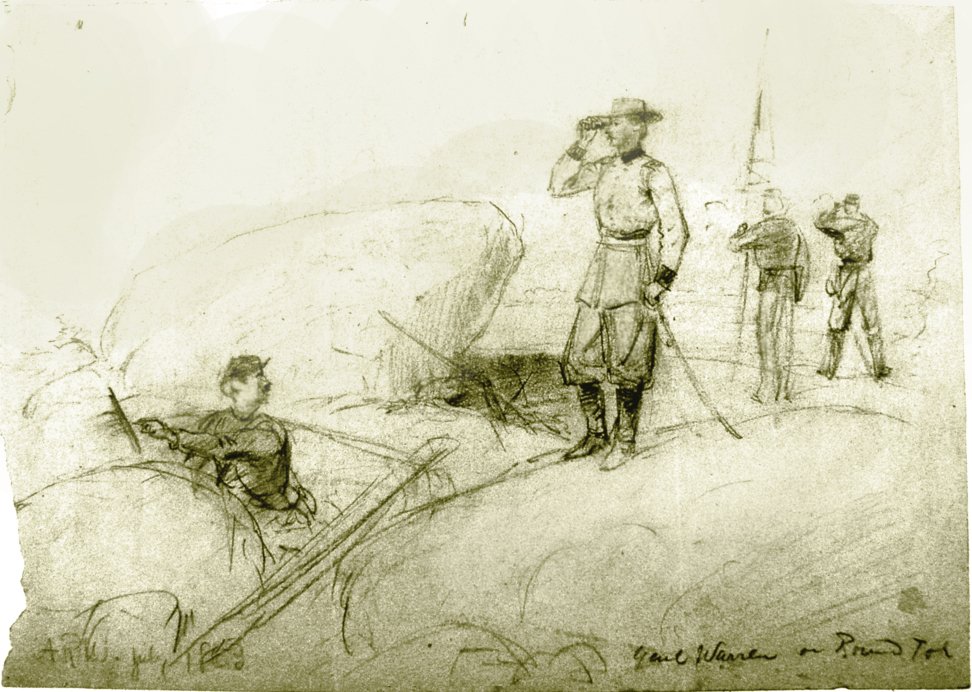

At first glance, Alfred Waud’s rendering of the view looking north from Little Round top may seem sloppy and made in haste. However, when its details are compared to a blow-up of Gardner’s photo of the same terrain, the accuracy with which Waud captured its salient features is simply astounding. Waud’s view actually contains details which escaped the glass plate negative, most notably the ground behind the boulder, and in the upper left-hand corner, Oak Ridge and the Railroad cut through Seminary Ridge.

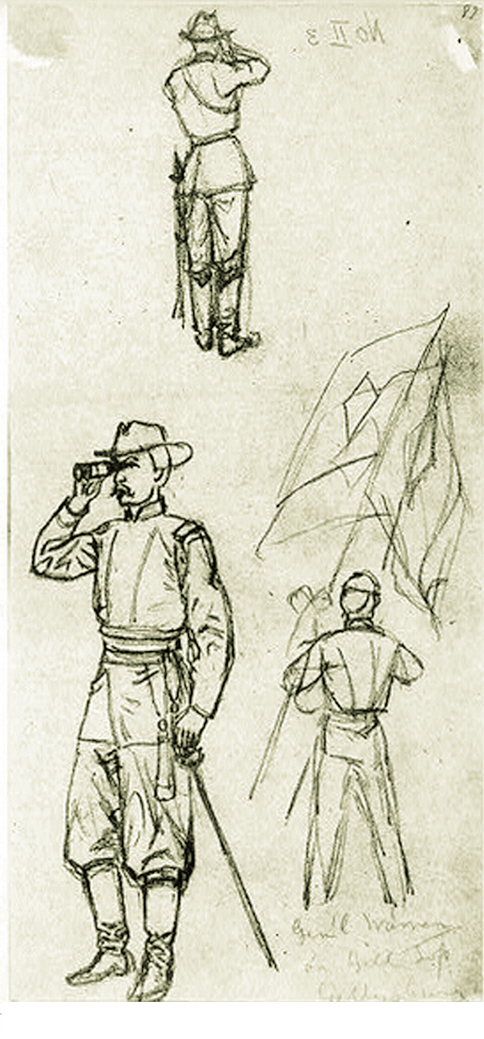

Mid-afternoon of July 2nd, Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, Chief of Engineers, accompanied Meade as he hurriedly rode from his HQ to the Emmitsburg Road to determine how much jeopardy his Cemetery Ridge line was in due to Dan Sickle’s having moved the 3rd Corp there without his permission. As they reached the location where Sickle’s had been posted earlier that day, shots were heard from the direction of that “little hill” (Little Round Top), and he sent Warren off to see what the “rattling” was all about.

At the time Warren rode up the slope to see whether, “…anything serious is going on,” its only occupants were a few Union signalmen. The Waud-Gardner comparison shows the view looking north that Warren had of Cemetery Ridge when he reached the signal station located on a shelf just below the crest. Warren was instantly shocked by the realization that if Confederates were to seize the hill, Meade’s Cemetery Ridge position would be out-flanked. He’d be left no choice but to abandon the field to Lee.

ARW July 1863, Genl Warren on Round Top

Genl. Warren on Hill Top, Gettysburg

It’s difficult to understand how neither Warren or Meade had considered this possibility prior to this fortuitous reconnaissance. To his credit, Warren didn’t hesitate but immediately sent to Meade for artillery and infantry to occupy the hill, and rode off in search of these himself.

One of the aides he’d sent on this mission rode up to where Col. Strong Vincent’s 5th Corp brigade had come to a halt on the Wheatfield Road. Vincent demanded to know what orders he carried, and, when told, took it upon himself to turn his brigade around and head up Little Round Top.

It was a near thing, and Vincent lost his life in the process. But because of the determined defense of his brigade and the heroic charges by the 140th New York and the 20th Maine, the Union forces managed to hold onto this key piece of real estate, and preserve Meade’s line.

Genl. Robinson’s fly at Gettysburg

This rather crude sketch is entirely untypical of Waud’s work. It shows the mundane activity in and near the tent of Brig. Gen. John Robinson. As Waud had to rely on the goodwill of officers for his sustenance, this everyday scene may have been produced as a way of ingratiating himself to one of his benefactors. A drawing of a tree is on the reverse (recto) side without any notation. It does bear a noticeable similarity to the “Sickles’ Headquarters” tree near the Trostle Farm that appears in two other drawings of his.

Gettysburg – Hill where Genl. Weed was killed – called by the soldiers the Slaughter Pen

The bare western face of Little Round Top rises behind the boulder strewn field of Devil’s Den. Recent logging had cleared its western face making the Rebel climb during the attack of the second afternoon much easier though it exposed them to a withering fire from the defenders above them. This is the sketch Waud was working on when photographed by Timothy O’Sullivan, Alexander Gardner’s assistant, on July 5th.

Sharpshooters from both sides plied their deadly craft from behind the boulder strewn landscape of Little Round Top and Devil’s Den during fighting on the second day. It was widely reported that it was a rebel marksman (possibly using a telescopic sight) who took the life of Brig. Gen. Stephen Weed.

As he stood among artillery pieces his brigade had just helped drag up the rocky east slope of Little Round Top, Weed was struck in the chest and died the next morning. While lying bleeding on the ground, the battery’s commander, Lt. Charles Hazlett, bent down to hear what Weed was muttering, and he was shot in the head and died instantly.

The two having been struck down while in such close proximity to one another gave rise to a report that it had been a sharpshooter who killed them. However, as with Reynolds, no evidence was ever given that would verify this claim.

Rebel marksmen, firing on Little Round Top

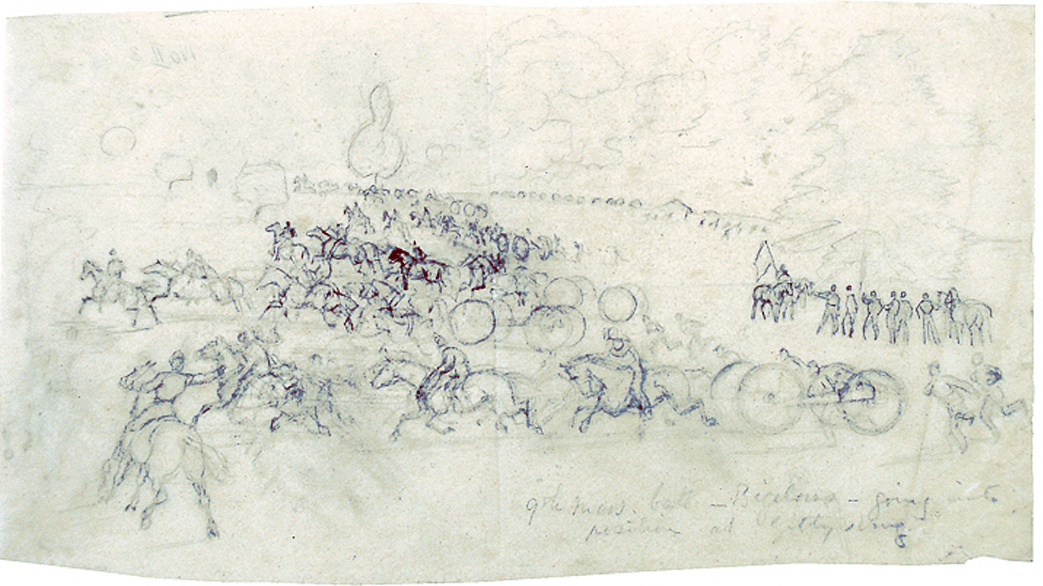

9th Mass. batt.– Bigelow’s – going into position at Gettysburg

Waud may have heard of the heroics of Bigelow’s battery, and chose to memorialize their brave action by picturing them going into position for their very first action. Clearly, it’s a considerably more impressive depiction than had he shown them after the sacrifices they made in their stand on the Trostle farm. The location of this deployment is on the left flank of the makeshift array of artillery Sickle’s assembled to protect the vulnerable salient contained in his line which developed from marching his Corp’s out to the Emmitsburg Road without permission. The battery is about to come into position facing the Wheatfield Road opposite the Stony Hill that stood between them and the Rose farm.

Entrance to Gettysburg, sharpshooting from the houses

The intersection of Steinwehr Avenue and Baltimore Street (Pike). Jennie Wade, the only civilian casualty of the battle, was kneading bread in a small cottage just out of frame on the right when she was shot through the heart by a stray bullet. Doubtless it was her death that drew Waud to this location. Two Union soldiers were using the upper bedroom as a gun position when she was shot. Their actions may have drawn the fire that killed her, but it could just as easily have been a missile from Union soldiers firing down from Cemetery Hill.

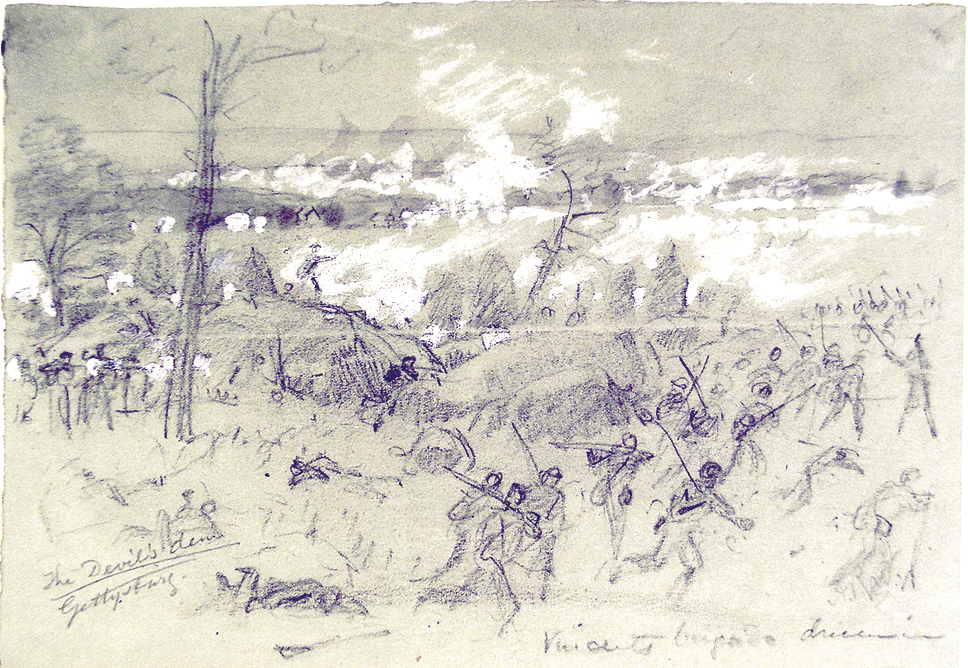

The Devil’s Den, Gettysburg Vincent’s Brigade driven in

The retreating Union soldiers could not have been in “Vincent’s brigade” since Col. Strong Vincent’s 1st brigade was fighting on Little Round Top at the time. Those pictured falling back were in 5th Corp’s 2nd brigade of “Regulars” commanded by Col. Sidney Burbank.

Part of Ward’s line Kershaw’s attack

Waud’s composition effectively conveys the extremely exposed position of Cpt. George Winslow’s battery posted on a knoll near the center of The Wheatfield while engaged in action on the afternoon of the second day. The Union regiment in the foreground might be the 17th Maine who were Winslow’s primary support for most of the action until both were forced to retire to avoid being overrun by Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw’s advance.

Preliminary sketch of drawing of Winslow’s battery in Wheatfield, Gettysburg

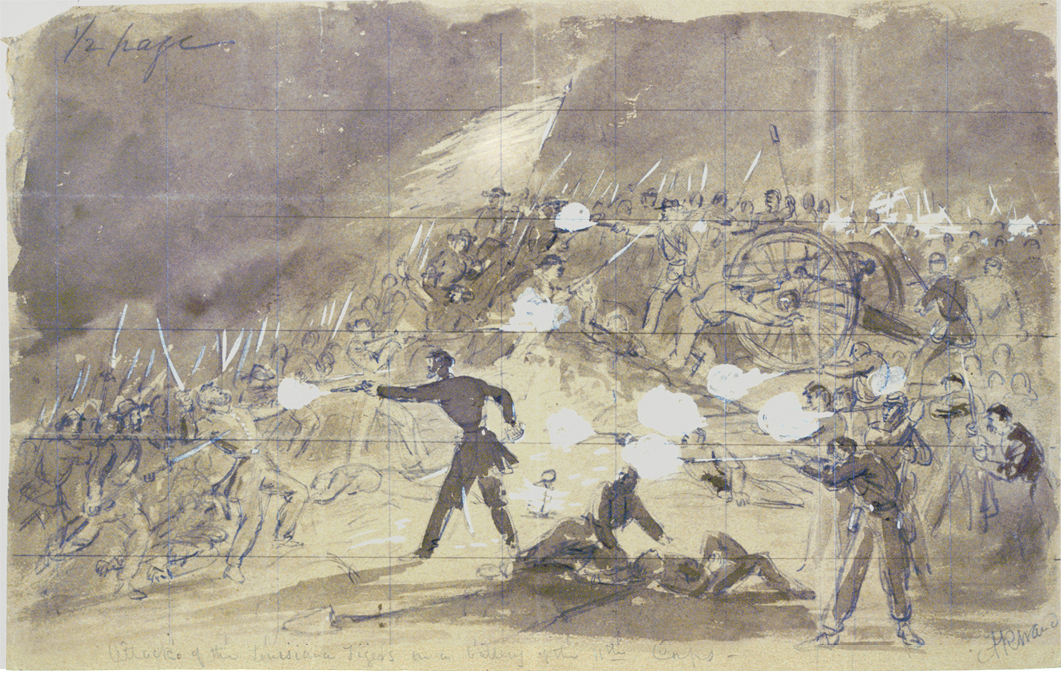

Attack of Louisiana Tigers on a battery of the 11th Corps

Confederate forces which fought their way to the top of Cemetery Hill at dusk on the second day are pictured overrunning Cpt. Michael Wiedrich’s battery. Waud’s note to the engraver advised he’d made it seem too dark. However, all contemporary accounts agree it was after sunset when the summit was reached.

Led by the “Louisiana Tigers,” this attack was scheduled to occur much earlier, and in concert with Longstreet’s assault on Meade’s left flank. However, Lt. Gen.. Richard Ewell’s 2nd Corp infantry did not actually “step off” until the fighting on the southern flank had nearly ended. Latter day analysis attributes the lack of cooperation between the two assaulting forces to their being located at opposite ends of an “exterior” line more than 51/2 miles long. Given that all messages were either delivered on horseback or by signal flag the distance separating the commanders made tactical coordination nearly impossible.

A contributing factor affecting their inability to coordinate action was the sloppy staff work which hampered Confederate Corps and Division commanders during the entire battle. Even Lee, who was recovering from some form of serious heart ailment, was not at his best, and exhibited an uncharacteristic willingness to leave critical decisions open to interpretation by his subordinates. This had to have been a factor in the breakdown as well.

(The horizontal and vertical lines were placed on the drawing by the engraver to aid in transferring it to an engraving plate.)

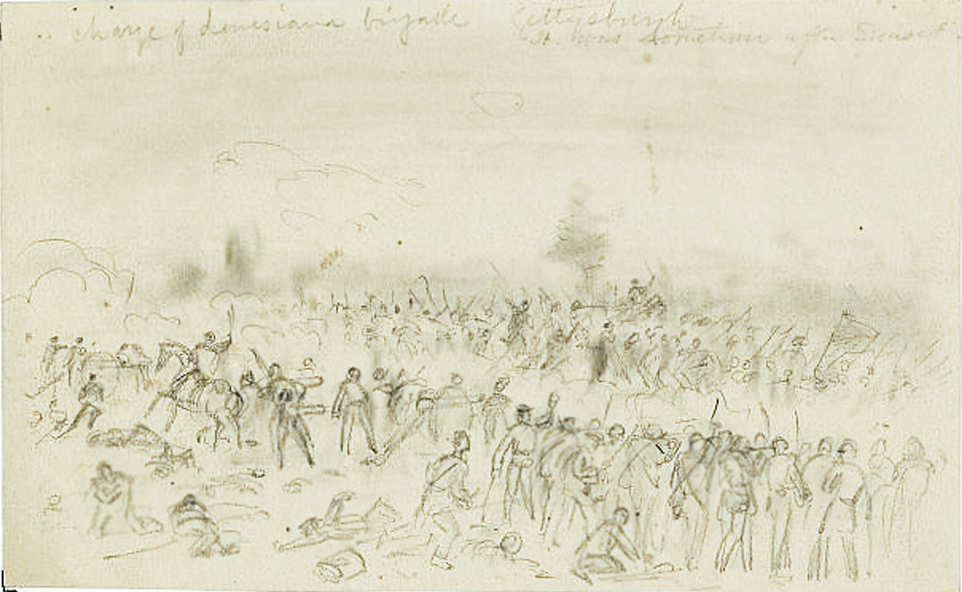

Charge of Louisiana brigade. Gettysburg (?) sometime after sunset

Waud almost certainly witnessed the Confederate assault on Cemetery Hill since he produced four sketches of it from different viewpoints. This one is located behind the defending Union battle-line, and may show Col. Samuel Carrol’s brigade fighting to take back Wiedrich’s guns that had been overrun earlier that evening.

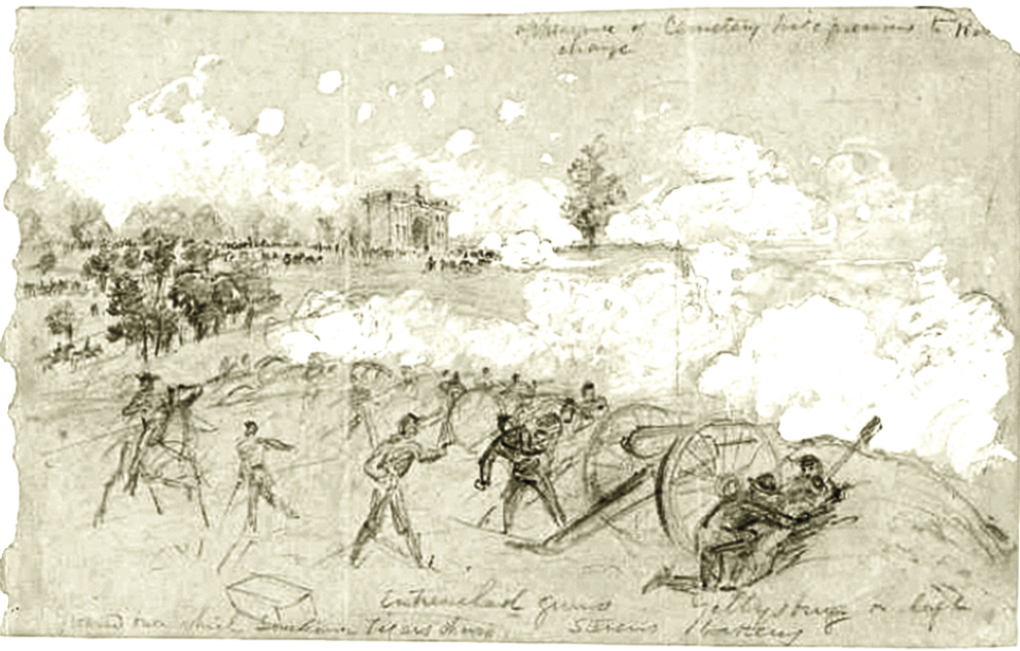

Appearance of Cemetery Hill previous to Pic(kett’s) charge

Ground over which Louisiana Tigers charged Entrenched Guns Gettysburg (?) Steven’s battery

Waud employed the device of painting on green or brown paper whenever he wanted to indicate explosions since puffs of white smoke would have been indiscernible on a white background.

In order to make their accent of Cemetery Hill, the Rebel assault was forced to change direction directly in front of Cpt. Greenleaf T. Steven’s Maine battery. Having to “right wheel” in such close proximity to his guns exposed their flank to a devastating fire which tore through the long ranks of infantry with terrible effect.

Smoke from batteries in front of Cemetery Gate House are from Weidrich’s and Rickett’s guns which would soon be overrun by the Rebel assault.

A panorama of the terrain that Ewell’s troops traversed attacking Cemetery Hill. Waud’s point of view is from above Steven’s Knoll on the southwestern slope of Culp’s Hill. The Cemetery gatehouse is at top/center. His sketch was probably made subsequent to the second days action since Steven’s battery isn’t shown, and the tranquil scene is devoid of any battle action.

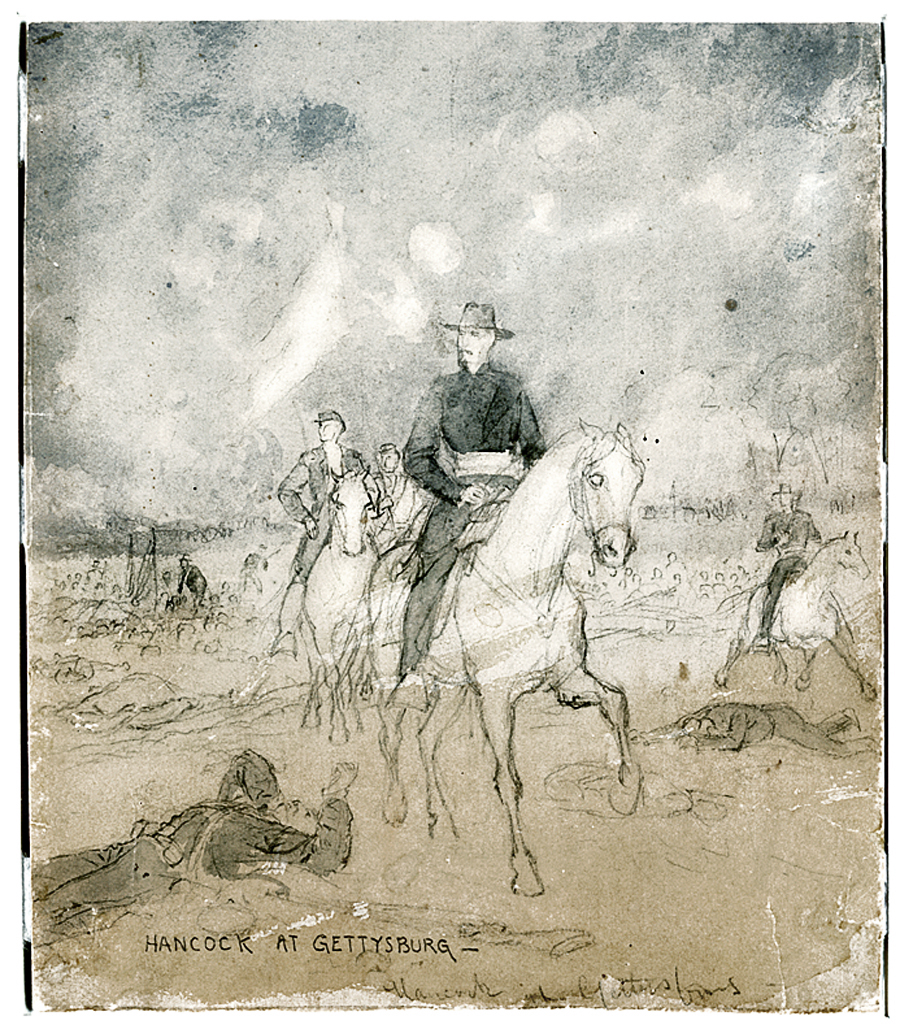

General Hancock riding length of 2nd Corps line prior to Longstreet’s advance, afternoon of July 3rd

During the artillery duel that preceded the climactic Confederate assault on July 3rd, in an act of bravado, Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock rode the length of his 2nd Corp line along Cemetery Ridge, hoping his demonstration would steel his men for the deadly work ahead. Seated in his saddle, he remained a conspicuous target. Near the end of the Confederate assault, a bullet struck the pommel of his saddle, driving a nail into his right thigh.

He refused to leave the field until after he’d determined that the attack had been successfully repulsed. As he lay propped against a tree, an aide slowed the bleeding with a makeshift tourniquet and Hancock survived. Eventually, he returned to command his Corp, but the pain he suffered while riding long periods often forced him to retire to the tail-gate of a supply wagon or ambulance while directing his men in battle.

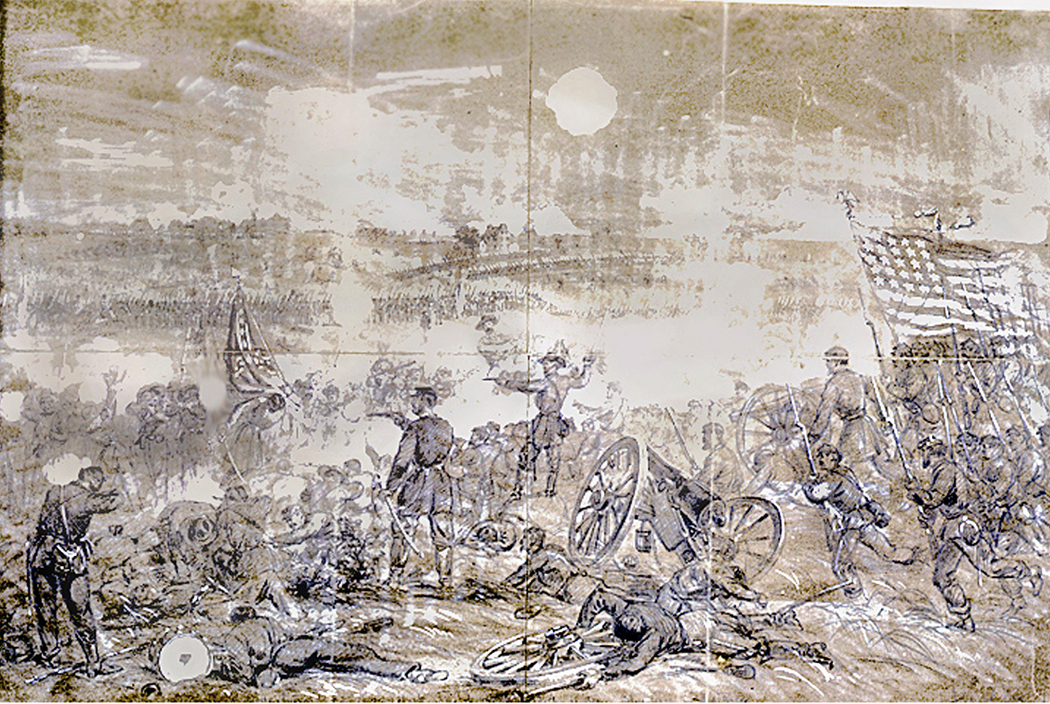

Battle of Gettysburg, Longstreet’s attack upon the left center of the Union Line, Blue Ridge in distance

Alfred Waud created this astonishing watercolor by lantern light the night after the repulse of the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble advance (“Pickett’s Charge”). It bears the distinction of being the first visual portrayal of Lee’s futile attempt to break through the center of the Union defensive position on the afternoon of the third day’s fighting.

Though both Virginia and North Carolina troops managed to cross the low stone wall in the foreground, Waud’s composition subtly implies they were successfully repulsed before reaching it. Published in Harper’s Weekly August 8, 1863.

Gettysburg

Quick wash study developed into watercolor of battery retiring after Pickett’s Charge

This is another example of Waud’s employment of a quick sketch to capture action for later use. Waud’s remarkable illustration transformed this hastily made “reminder,” devoid of any detail, into a watercolor that displays how completely spent the survivors of a Union battery seem as they retire from Cemetery Ridge following the repulse of “Pickett’s Charge.” His use of color raises the question of whether he planned to work this into a finished artwork at a later date.

Near the Cemetery, Gettysburg — Retiring disabled Artillery

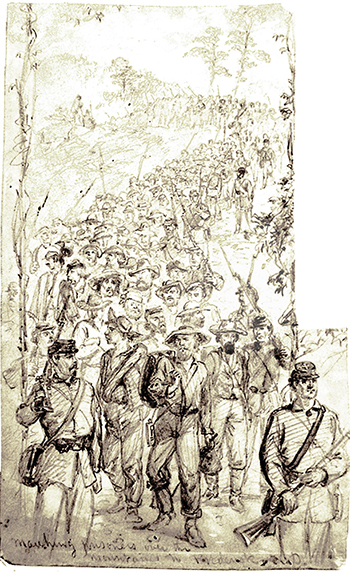

Marching prisoners over the mountain to Fredrick, MD

Dejected Rebel soldiers whose war has ended. Though they managed to survive the battle, the majority would not survive the horrible conditions they’d soon be exposed to in Union prisoner of war facilities. After the war a great deal of noise was raised denouncing the deplorable condition of Confederate camps, but hardly any attention was given to the equally deplorable conditions of their Federal counterparts where tens of thousands died of exposure, starvation, disease, and murder (by both guards and fellow prisoners). Published in Harper’s Weekly week of August 15, 1863.

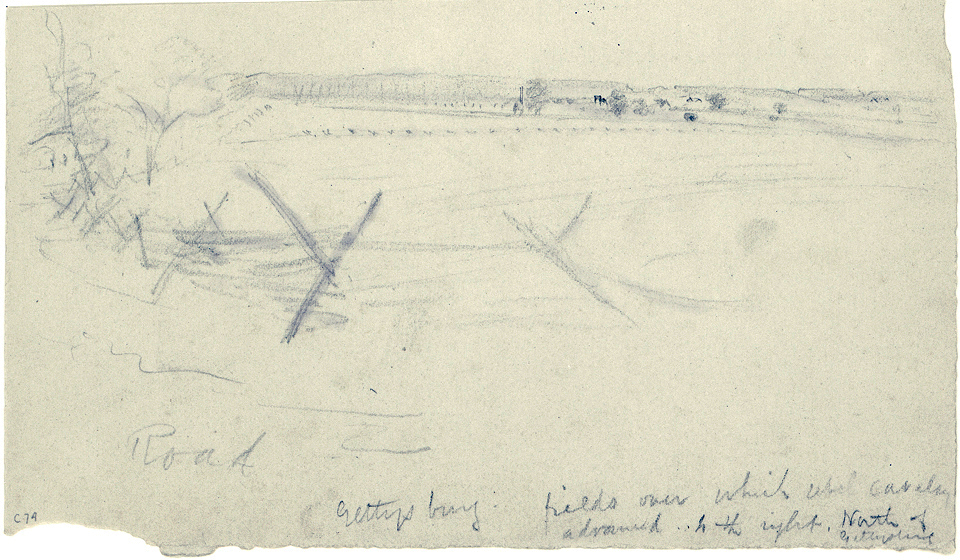

Road, Gettysburg fields over which rebel cavalry advanced on the right, North of Gettysburg

It was on this field that the newly minted Brigadier General, George Armstrong Custer first made a name for himself leading a charge of his Michigan cavalry that successfully repelled the Rebel cavalry of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. The minor action unfolded northeast of Gettysburg near Hunterstown during the late afternoon of July 3rd.

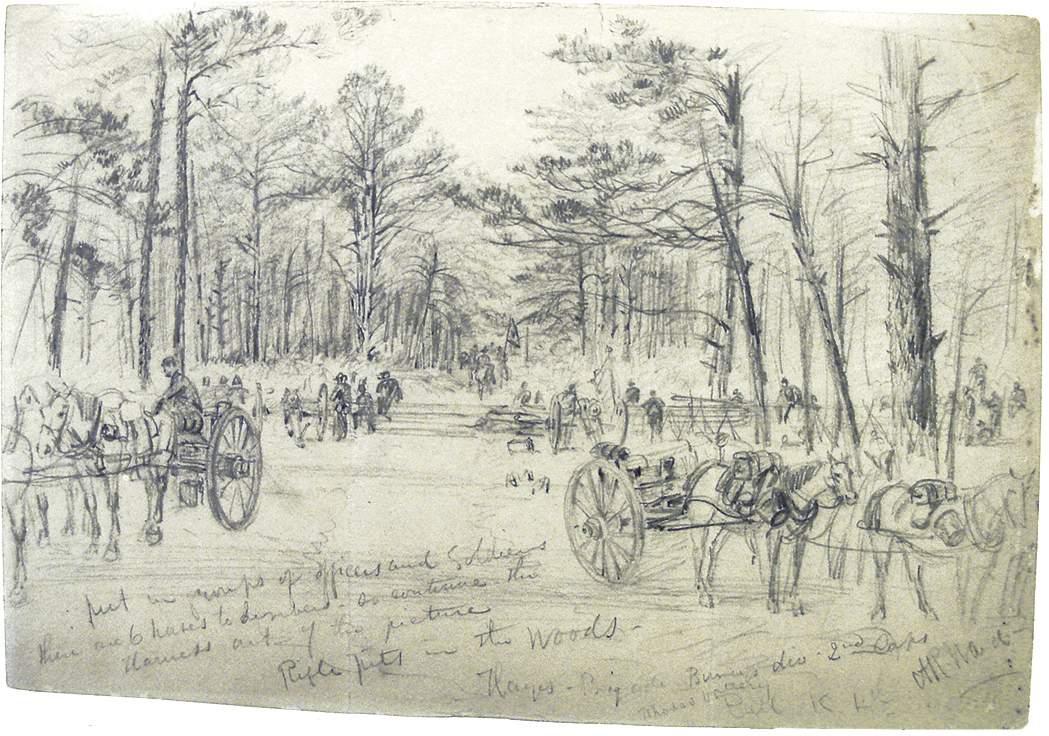

Put in groups of officers and soldiers

there are 6 horses to limbers – so continue the Hays Brigade Birneys div – 2nd Corps AR Waud

horses out of the picture Bull KL

Rifle pits in the woods Thomas battery

A somewhat curious drawing considering the time Waud had to devote to it. The battery of Lt. Evan Thomas was engaged on both July 2nd & 3rd, but did not figure prominently in the action nor was its performance particularly noteworthy. With dozens of battery’s suffering terrible loses, it’s strange that Waud chose to picture this one.

Waud’s notation attempts to specify which command Lt. Evan Thomas’ Battery supported during the second day of battle, however, Hay’s was a 2nd Corp brigade, and Birney’s Div. was in the 3rd Corps. To confuse things further, Thomas was posted on Cemetery Ridge in support of 2nd Corps commands fighting on the Emmitsburg Road.

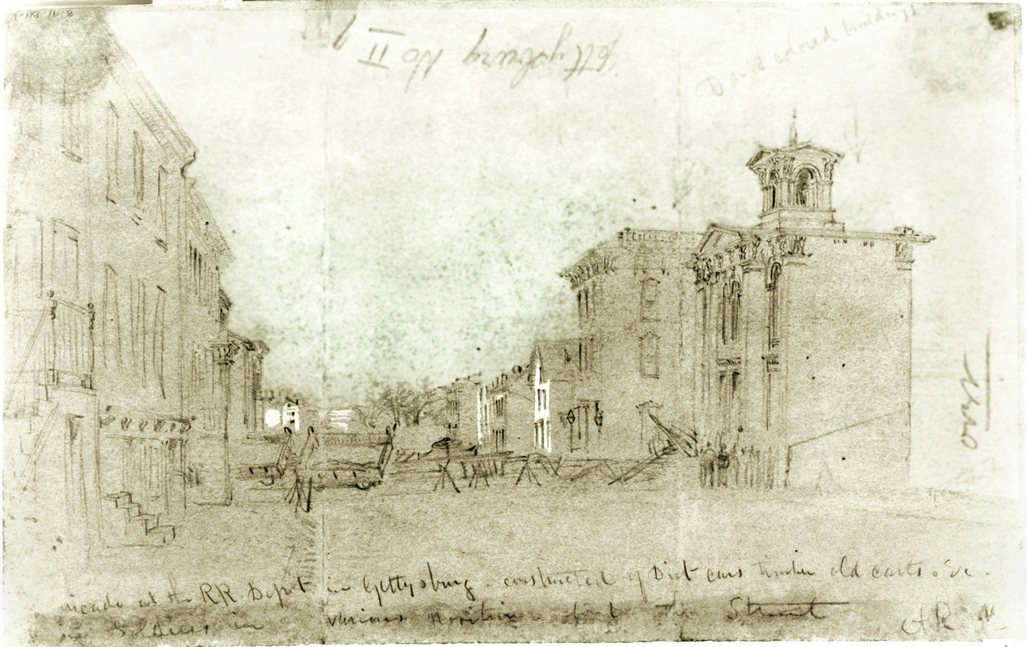

Inverted Gettysburg No II Dark colored buildings

[Bar]ricade at the RR. Depot in Gettysburg constructed of Dirt cars, timber, old cars, & c.

Soldiers in various positions about the street

Waud’s training as a theatre designer is on excellent display in this street scene leading to the R.R. Depot. The barricade was constructed by the Rebels, though what it was meant to bar remains a mystery. After the first afternoon, they exercised complete control of the town and the territory north of it, making it highly unlikely any Union troops could have posed a threat to this part of the village.

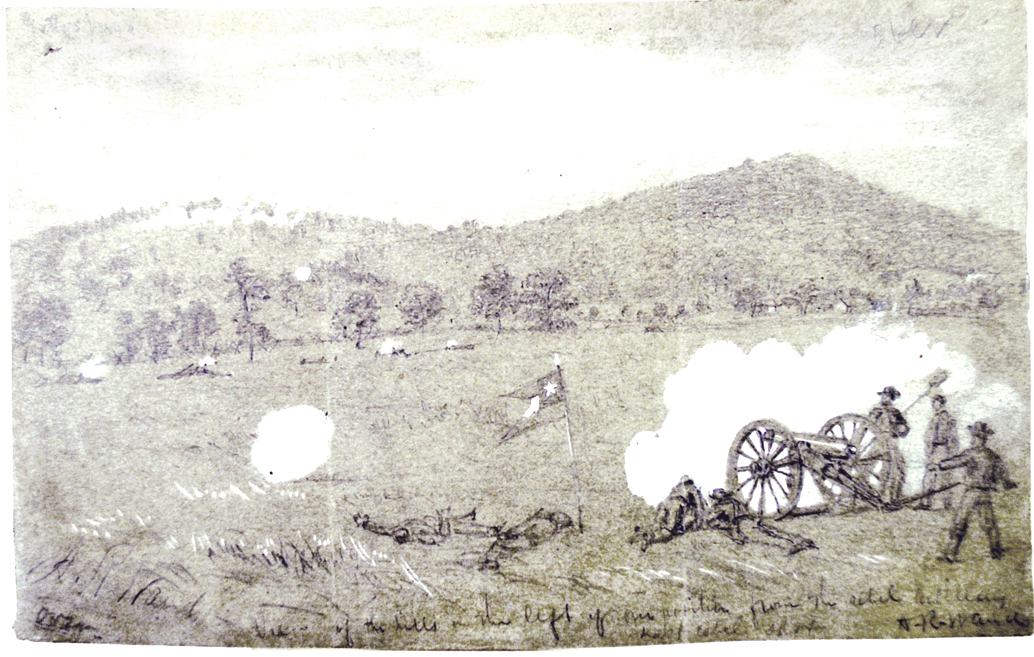

Gettysburg – View of the hills on the left of our position from the Rebel artillery – Last Rebel shot

While there was no infantry action on July 4th, there were sporadic instances of artillery units firing upon one another. Smoke from Union batteries rises from the crest of Little Round Top as Rebel guns in the middle ground join a lone Texas field piece in what was possibly a final salute. Later that night, Lee withdrew his army from Gettysburg and began the painful retreat back to Virginia.